Last week, Grantland’s Wesley Morris published a fantastic article about what he called “the quiet queering of professional sports.” In it, he talks about Brittney Griner, the 6’ 8” college phenom and WNBA number one pick who is openly gay, and how the new generation of athletes seems more comfortable with their sexuality, even when it veers into the historically-less-comfortable territory of ambiguity or androgyny. It’s simply not that big a deal to them anymore, and they feel perfectly fine expressing this ambiguity with their fashion choices.

So, too, have a number of NBA players embraced what can only be described as a flamboyant sense of style, whether it’s Russell Westbrook and his loud, retro color schemes; Lebron and his tiny man-purse; Dwayne Wade and his spray-on sweaters and skin-tight, gerbil-colored pants; Tyson Chandler and his fedora-blouse-Capris -and-laceless-combat-boots ensemble; or just about everybody with their lensless horn-rimmed glasses.

The point is that there is an ongoing trend of male athletes – who identify as straight – making the types of sartorial decisions that would have previously raised questions about their sexual orientation. Straight athletes are no longer afraid to rock a sassy outfit to a postgame press conference, and it’s hard not to see it as a direct result of the recent sea change in public opinion about the issue of homosexuality. A total of nine states now legally recognize gay marriage, and the ongoing efforts of gay rights advocates to de-stigmatize the LGBT community are finally starting to pay tremendous dividends. Even the POTUS has publicly expressed his support.

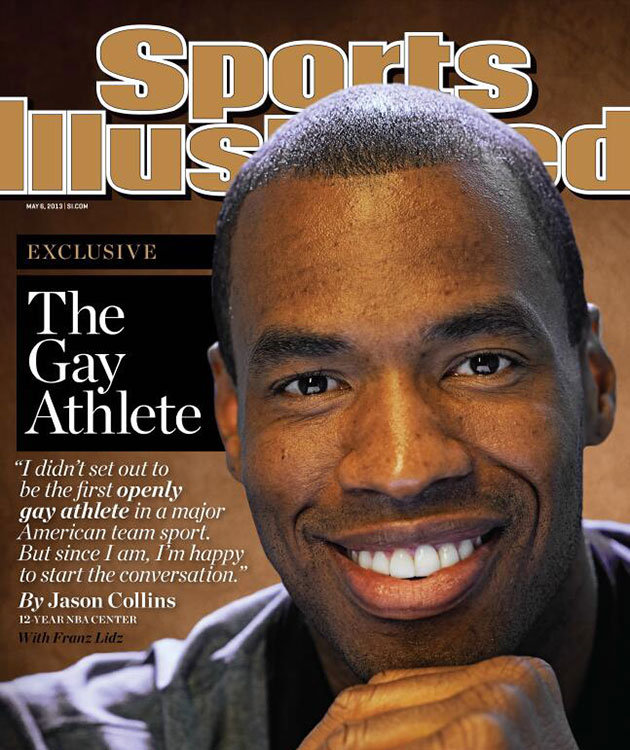

A few weeks ago, former Ravens player Brendon Ayanbadejo told the Baltimore Sun that he believes as many as four NFL players could come out soon in an effort to create solidarity among professional athletes around the issue of gay rights. That hasn’t happened yet, but yesterday, veteran NBA journeyman Jason Collins dropped an H-bomb on the sports world when he became the first openly gay athlete currently playing in one of the four major professional sports.

The reaction to his announcement among his NBA peers has been overwhelmingly positive. Even high-profile players like Kobe Bryant, Steve Nash, Tony Parker, and others took to Twitter yesterday to offer their support, but there were plenty of mixed and negative reactions as well to remind us that there is still long road ahead.

Miami Dolphins wide receiver Mike Wallace Tweeted: “I’m not bashing anybody don’t have anything against anyone I just don’t understand it” and “All these beautiful women in the world and guys wanna mess with other guys SMH…”

The Tweets were quickly deleted, and Wallace later posted an apology, either because he soon realized they weren’t going over well or because someone in the Dolphins organization caught wind of it, or both. But, somewhat unwittingly, Wallace’s Tweets ignited a debate about what exactly constitutes “homophobia” these days. Is it relegated to overtly hateful speech or threatening comments, or does it include the type of ignorance and/or general disapproval reflected in Wallace’s Tweets? America has always struggled with where exactly to draw the line between free speech and hate speech.

For instance, how do we categorize comments like the ones we saw from Warriors coach Mark Jackson and ESPN analyst Chris Broussard, each of whom echoed the sentiment that homosexuality is considered a sin in the Christian community? (Note that ESPN later issued a public apology and required Broussard to do the same.) Is it hate-speech, or is it more accurate to simply call them condescending and hypocritical?

For starters, it bears mentioning that Collins, in his Sports Illustrated article, says that he was raised and instilled with Christian values, namely the ones about tolerance and understanding. Huffington Post blogger Matt Yoder, who is also Christian, had this to say in his response to his announcement:

“I’m a Christian. I stand with Jason Collins. I feel the need to state this plainly because we live in a world where Christians have by and large failed the LGBT community and failed to follow through on the words and ministry of Christ. As I read column after column today on Jason Collins coming out I felt more and more persuaded to say something so that the only Christian voice in this discussion isn’t one that condemns.”

If anything, the reactions to Collins’ coming out is a good barometer for just how far we’ve come in recent years. Most people today don’t think it’s a big deal, but there’s a reason why more gay athletes haven’t come out yet. In his 2007 memoir Man in the Middle, former NBA journeyman John Amaechi became the league’s first player to come out retroactively, and his revelation caused much more of a stir among players, coaches, critics, commentators, and fans as recently as five years ago.

Amaechi’s book subsequently spurred a succession of awkward interviews in which the sports media grilled high-profile players like Lebron James about how they might react to a gay teammate.

“With teammates you have to be trustworthy, and if you’re gay and you’re not admitting that you are, then you are not trustworthy. So that’s like the No. 1 thing as teammates — we all trust each other…. It’s a trust factor, honestly. A big trust factor.” Lebron said.

Jamal Crawford said that it would probably be “awkward” in the locker room. Eddie Jones went a step further and said that the other teammates would likely ostracize a gay player. When asked if he (Amaechi) would have been accepted, Troy Hudson said “probably not.” Tracy McGrady conceded that he would be cool with it “as long as you don’t try it with me.” Shavlik Randolph said “As long as you don’t bring your gayness on me, I’m fine.” Steven Hunter said that he sees “a lot of sick, perverted stuff about married men running around with gay guys and all types of foolishness…”

There was an obvious undercurrent of homophobia to many of the responses, but the nastiest vitriol came from Tim Hardaway, who told a Miami radio station “I hate gay people. I am homophobic. I don’t like it. I don’t think it should be in the world or in the United States.”

I always thought using the indefinite pronoun made “it” seem the smoke monster from Lost, but nevertheless, the unsettling part was that you got the sense Hardaway was just (tactlessly) saying what many other players were thinking or not so eloquently skirting around.

For Hardaway, a P.R. shit-storm came barreling in over the horizon, and after drawing the ire of several prominent LGBT groups, the NBA immediately distanced itself from him, his endorsement deals fell through, and he was soon forced to embark on a public apology/damage control tour. But it was precisely this backlash to the backlash that seemed to signal the turning tide of public sentiment, and Amaechi’s book was arguably the landmark moment that paved the way for Collins. The ensuing dialogue proved that it was no longer okay to spew the kind of vile hatred Hardaway’s response represented.

To his credit, Hardaway eventually became a spokesman for gay rights in 2011, although to some, including Amaechi, his 180-degree turn seemed a bit disingenuous, and it’s tempting for the more cynical among us to dismiss the positive reactions to Collins announcement as nothing more than a kowtowing to political correctness, or worse, a fear of incurring fines and P.R. nightmares and being forced to issue tepid apologies.

But at the time of the book’s release in 2007, there were already a number of current and former players who boldly supported the crazy notion that gay and straight men could coexist and thrive together on a professional sports team. Charles Barkley, Shaquille O’Neal, Grant Hill, and numerous others all echoed this sentiment in their own way.

In 2011, the NBA sponsored a commercial called “Think B4 You Speak” featuring players like Jared Dudley and Grant Hill urging young people to quit using the word “gay” in a derogatory fashion among their peers. Earlier that season, Kobe Bryant had been heard calling a referee a “faggot” after he was given a technical foul and was subsequently fined $100,000 by the league and forced to issue a public apology. The league, in turn, also issued an apology to “our friends in the LGBT community.” It also bears mentioning that, shortly after the video premiered, then-Phoenix Suns president and CEO Rick Welts (now Warriors President) announced that he was gay. Welts also spoke out in support of Collins yesterday via Twitter.

It seems fitting that the NBA would be the first of the four major sports to boast an openly gay player. The history of the NBA paralleled the civil rights movement, and the world of professional sports is one of the few remaining battlefronts in the new civil rights struggle of our time. Bill Russell was a phenomenal player, but he was also an outspoken civil rights activist in the 1960s. When Russell entered the NBA, there was a cap on the number of black players allowed in the league (15), and up to this point, there has been an unspoken rule against gays in professional sports. Jason Collins just altered the course of history for future generations of athletes.